| News |

Soba noodles

by Raphael

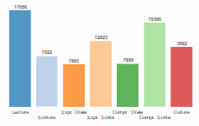

Wholesome, nutritious soba noodles are one of the most popular dishes in Japan. The firm, yet smooth, noodles are eaten all over Japan, and the light, but satisfying meal has been a popular form of affordable fast food ever since it was created in the Edo period. Today, around 35000 soba restaurants exist in Japan, feeding all types of people, from the humble to the connoisseur.

As with many Japanese foods, each region has its own specialties for preparing and serving soba. Ibaraki Prefecture is famous for its quality buckwheat. Buckwheat in Japan is almost entirely used for soba noodles, though there are a few other foods that are also made with buckwheat. Yamagata Prefecture is home to a soba festival that allows dozens of people to enjoy soba from the same long platter. In Iwate Prefecture, there is a popular competition-style way of eating soba known as “wanko-soba,” where customers have one mouthful of noodles served up into their bowls at a time, which they slurp down almost as soon as they are served.

Soba is a part of important Japanese traditions such as the New Year celebrations. In Japan, long soba noodles are consumed on New Year’s in order to impart a long life to the family who eats them. Other traditional foods can be made with buckwheat, which is simply called “soba” in Japan. Soba-gaki paste is made by pouring hot water over buckwheat flour. This can be eaten as it is, seasoned lightly with soy sauce, or formed into dumplings which can be eaten alone or added to soup.

Buckwheat is a plant that is relatively easy to grow, and which matures quickly. It is sown in the summer and harvested in October or November. To make soba noodles, buckwheat must be ground to remove the black hulls, mixed with wheat flour or other ingredients to help it stick together, and then kneaded quickly until it congeals into a large lump. If the dough is not kneaded quickly and lightly under the noodle maker’s hands, it will not properly absorb the small amount of water added to the flour. The dough is then rolled out by the noodle maker to a thickness of about 1.2 millimeters. Care must be taken not to tear the dough in the rolling process, and great skill is also needed to judge the thickness of the dough without touching it with one’s hands. The dough is finally folded over and chopped into uniform strands. These are cooked in hot water for only thirty seconds, drained, and then served to the customer.

The variety of soba noodles that one can enjoy in Japan is nearly limitless. Soba noodles come in a number of different flavors and aromas. Ni-hachi soba is made from two parts wheat to eight parts soba. Sarashina noodles are white and translucent, while Inaka noodles are brown and firm. Dattan noodles have become popular because they are highly nutritious. No matter what the style of noodles, the popular ways of serving soba remain largely the same. Soba is sometimes served cold, with a savory sauce known as “tsuyu,” made from bonito, soy sauce, sweet rice wine, and other ingredients, seasoned with wasabi and scallions to the customer’s taste. Soba can also be served hot, in a soup made from broth mixed with tsuyu. Different kinds of toppings are also popular. Kitsune, or fox, soba comes with fried tofu on top, whereas tanuki, or raccoon dog, soba comes with a scattering of morsels of tempura batter. Tempura soba is popular too, and generally features deep fried prawns as a complement to the noodles.

There is an accepted set of manners for consuming soba. The noodles should always be slurped with gusto. Slurping in the Japanese fashion enables the customer to enjoy the aroma of the soba noodles, which in turn enhances their flavor. Scientific tests have proven that the air taken into the mouth while slurping noodles helps transmit the aroma up through the nose, enhancing the eating experience. The first mouthful of soba noodles should be taken without the use of tsuyu sauce, so that the diner can appreciate the unadulterated taste of the noodles themselves. Then, noodles should be dipped only partway into the tsuyu, to achieve a balance of flavor where neither noodle nor sauce dominates. When the noodles are finished, the hot water the noodles were cooked in may be served. This can be used to dilute the remaining tsuyu so that the customer can drink it. None of the dish need be wasted.

Buckwheat has been grown for thousands of years in Japan, to help poor farmers survive when their rice crop was heavily taxed. Originally, it was made into dumplings or cooked in the hull, but when Edo (now Tokyo) was made the capital of Japan, street food became popular, since the many laborers developing the city were far from home and needed to be fed. Although buckwheat flour was originally found to be difficult to work with in comparison with the wheat flour used in udon, its relatively low cost and easy availability made it attractive as a food source. Some cooks discovered that steaming soba kept it from breaking apart, while others realized that mixing soba and wheat flour together allowed it to stick together. Finally, soba noodles were born. When coupled with the strong soy sauce developed in Edo, the dish was a perfect combination.

Although automation in the 1920s made machine-formed soba noodles the norm, there are still some noodle makers who labor to produce delicious, hand-made noodles. Soba was once a food for poor farmers and laborers, but centuries of refinement have elevated soba to an art form on par with other Japanese cuisine. Soba aficionados can enjoy painstakingly-prepared, elegant noodles while busy businessmen and laborers can still enjoy a quick mouthful of buckwheat noodles at a standing counter in a train station or at a table in a local restaurant. Simple, versatile soba noodles are enjoyed by all kinds of people in Japan.

Photo credits:

| Aucun commentaire |