| Actualite |

Tanabata Matsuri

par Xehanort

"You two, why wouldn't you start working soon?"

Such was Tentei’s (天帝), God of the Sky, question who had ceaselessly repeated this phrase for many weeks. More precisely, since love had bloomed between Orihime (Vega star), a weaver goddess, and Hikoboshi (Altair star), a mortal herdsman.

"Yes, tomorrow we will."

Their answer angered the God of the Sky. From this anger, a new legend was born. Every year, for centuries now, the Japanese commemorate the Tanabata legend. But what are the origins of the ever-flourishing Tanabata legend? To what decision did the God of the Sky come to? Is this legend still at the heart of Japanese culture?

Origins

This festivity originates from a Chinese festival Qīxī (七夕 - the night of the seventh month). This festival is also called Qiqiao jié(乞巧节 - the festivity where young maiden show their abilities). Some people say that the word Tanabata came from the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese characters "七夕 ". Others say that the name of this legend could also come from the Miko (巫女), young girls in service to a Shinto sanctuary, who would weave near water a special costume called Tanabata (棚機).

During the Heian era (平安時代 - 794 -1185), the legend is introduced by the imperial court of Kyôto, which is under the control of the 50th emperor, Kammu. The legend then spread throughout the country during in the Edo era.

The Legend

Many versions of the legend of Tanabata exist, but the framework is similar in all of them. For example, a weaver Goddess and a mortal herdsman are usually the main characters.

Orihime, daughter of the God of the Sky, was weaving magnificent outfits that pleased her father greatly. Endlessly weaving on the edge of the Milky Way, Orihime became sad after thinking she wouldn’t meet anyone who could make her fall in love. The god of the Sky was happy with his daughter’s work but he worried about her growing moroseness. And so, he started looking for a companion for his daughter.

On the other side of the Milky Way, there was a hard-working shepherd named Hikoboshi. The shepherd took great care of his sheep. He regularly washed and fed them delicious grass. The God of the Sky decided to engineer a fateful encounter between Hikoboshi and Orihime. The troubled shepherd then said: “God, for a person like me this is like a dream. I accept with gratitude”. Orihime also approved of Hikoboshi and they got married.

They were happy together. They passed their time by talking from dawn till dusk on the very edge of the Milky Way. The God of the Sky witnessing this asked them a question:

"You two, why wouldn't you start working soon?"

"Yes, tomorrow we will."

But, they never started working. They preferred to pass their time together, idle on the edge of the Milky Way. Since Orihime didn’t weave anymore, dust began to pile up on the weaver-loom and no more cloth reached the sky. Likewise, Hikoboshi’s sheep’s were getting thinner and began to die one after the other.

Displeased, God separated them. However, moved by his daughter’s tears, God granted them one night per year. So now, each year, the lovers get to be together on the night of the seventh day of the seventh month. Up to this day, we can see them twinkle on each side on the Milky Way, waiting with anticipation the night of their reunion.

At the end of the legend, it is said that without a bridge linking the two sides of the Milky Way, the two lovers could never meet. Orihime, drowning in sorrows, cried abundantly. A flight of celestial magpies came to her and promised her to build a bridge with their wings to allow the lovers to cross over the edges of the Milky Way. Unfortunately, the magpies cannot come if it rains. So if it rains on the night of Tanabata, the lovers have to wait another year before they can embrace each other.

Variants

The legend has different versions but the framework remains the same. One of them tells us that the God of the Sky had seven daughters. Orihime was the youngest one. She weaved celestial brocades, which regulated the days and the nights and even the change of the seasons. Bored by her work and dreaming of a passionate love she came down to earth. There, she encountered a shepherd. Love sprung out between them and so did two children. They believed nothing could ever separate them. However, after hearing what his daughter had done, Orihime’s father burst in anger and sent a genie to get her. Orihime fell into great despair. Hikoboshi, the shepherd, in a fit of temper, quickly went after her carrying their two children in baskets.

At the sight of the shepherd, Orihime’s mother created, with a wave of her hand, a magic river, the Milky Way, to prevent the lovers’ reunion. Nevertheless, the cries of the two lovers and their children convinced the God of the Sky to let them see each other one day per year.

In other versions, Hikoboshi used a stratagem to get to the Heavens. He suspended his children’s basket to stems and presented them to the Heavens pointing out that they would be better with their mother. The Gods (there are many gods depending on the version) accepted his plead and started to pull on the stems. What they didn’t know was that Hikoboshi had attached himself firmly to the stems beforehand. The God of the Sky welcomed his son-in-law. From this moment, Orihime started to neglect her work and her father grew angry. He decided that it was time to separate the lovers. Embarrassed by his daughter’s tears, he allowed them to see each other for one night only. On this night, a bridge of stars is formed in the sky.

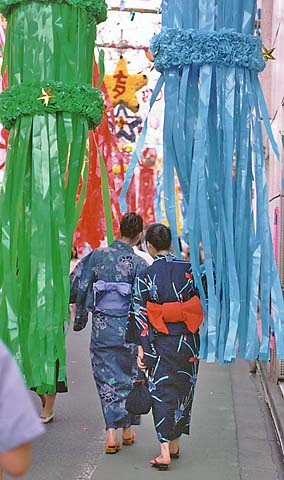

A popular festival

In the end, this is a legend for the romantic: a forbidden love story. Japanese are fond of love stories and romanticism. The story touches everyone, from the eldest to the youngest and not only the ones in love. Going out wearing a Yukata (a thin summer kimono worn by men and women), decorating some bamboo leaves and praying for good weather are all ways to celebrate the stars festivity. Other current activities in Japan, at this period of time, are to write out wishes on a Tanzaku (small vertical card originally used to write poems) and hang paper ornaments in trees. It is told that these wishes, personal (like success in school) or romantic, will come true. The bamboos and the other decorations are then burnt or thrown in the water the following day, or at midnight.

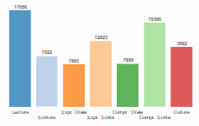

It is common to see parades and fireworks in the afternoon and evening. The Sendai festival, taking place on August 6,7 and 8, is the biggest one in the country. It is preceded by the Kanagawa festival, taking place on July 6,7 and 8.

This three-part video is a good example of the ambiance during the Tanabata festivities. From parade to fireworks, with décor conception in between, no less than 25 minutes of discovery.

Elections of a “ Miss Tanabata”, contests, outdoor catering and games are all organized. Tokyo Disneyland often celebrates the Tanabata with a parade of whishes with Mickey in the role of Hikoboshi and Minnie in the role of Orihime. Therefore a festive atmosphere is a must.

Decorations

Many decorations for the festivity of Tanabata exist: each one of them having a different use and signification. Those passionate of Japanese culture will recognize them easily.

Firstly, the «Tanzaku" (短冊) mentioned earlier: small vertical card originally used to write poems. Essentially used today to write our most precious wish during this festivity.

The "Orizuru" (折り鶴), origami (folding paper art) paper crane supposed to bring longevity, good health and security for one’s family.

The "Kinchaku" (巾着) bag resembling a purse; brings good business.

The "Toami" (投網): a sort of net that would bring good fishing and harvests.

The "Kuzukago" (くずかご): a garbage bag bringing cleanliness and thriftiness.

The "Fukinagashi" (吹き流し) are the streamers Orihime would have used to weave.

The "Kamigoromo" (紙衣) believed to bring quality sewing, and defense against accidents and bad health.

To this list, it fits to add the "Kusudama" (薬玉) which often decorates the upper part of the streamers. A Sendai shop owner had the original idea in 1946. His original design was based on a Dahlia flower.

There is also a traditional song:

ささのは さらさら - Sasa No Ha SaraSara – The bamboo leaves murmur

のきばに ゆれる - Nokibani Yureru – and oscillate on the eaves

おほしさま きらきら - Ohoshisama Kirakira – The stars twinkle

きんぎん すなご - Kingin Sunago – Like gold and silver sands

ごしきの たんざく - Goshikino Tanzaku – On colored paper

わたしが かいた - Watashiga Kaita – I wrote

おほしさま きらきら - Ohoshisama Kirakira – The stars twinkle

そらから みてる - Sorakara Miteru – and contemplate me from the sky

Conclusion

In conclusion, though the Tanabata festivity is less popular today, it is still one of the pillars of the Japanese summer culture and a major event for the many towns that organize such a celebration. It is a festivity for all with shows, passion and magic. A festivity where we have fun, where some people dream of love and where some people exude their love for one another. Finally, this love unites a nation under the stars, which fall into their eyes and make them shine like a thousand flickering lights.

Photo credits:

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:TanabataTokyo.jpg

- http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%82%A4%E3%83%AB:MoriokaShoppingMall.JPG

- http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E4%B8%83%E5%A4%95

| Aucun commentaire |